Wow, you might be thinking, do they really mean every malted barley on Earth? Yes, we do mean it. We’re embarking on this massive undertaking so you only have to look in one place to find the perfect brewing malt for your next brew.

Farmers and brewers are breeding new varieties of malt every year, but that doesn’t mean you have to go into picking a malt for your next original recipe completely blind. We’re creating the most comprehensive list possible so you can have a better idea of how to select your next malt.

So let’s not waste any time. What exactly is malted barley, how does it change your brew, and just how many varieties are there? (Spoiler: So many.)

If you already know everything you need to know about malted barley, and you just came here for that complete list, we got you. Click here to view the spreadsheet we built that contains not only every brewing malt, but also hops, yeast, extracts, and adjuncts.

What is Malted Barley?

Cereal might not be the first thing you think of when you get ready for your next brew day, but it’s absolutely crucial for lagers and other beer styles. That’s because the malts we rely on for flavor and color typically come from barley, which is the most widely adapted type of cereal grain in the world.

While any grain can be malted, we prefer barley for a few reasons. The most important reason is its ability to retain a husk through harvesting, milling, and handling. Keeping the husk around allows barley to:

- Regulate its water intake during malting

- Slow its sprouting during malting

- Maintain the grain shape

Basically, the durable husk keeps barley from becoming a gummy, sticky mess during the malting process and beyond. You don’t want your cereal to gum up your mill while you’re crushing malts. So while we can make malts from wheat, rice, and rye, brewers tend to prefer barley.

Now you know brewing malt requires barley (or some type of cereal grain). So what makes it an actual malt?

Malting is when we allow grains to partially germinate (the technical term for sprouting) and then dry and/or heat the kernels. This tiny bit of germination unlocks sugars, starches, and protein stored in the seed so your yeast can feast during fermentation. The drying and heating stops germination and keeps the kernels from growing into new plants.

Once the grain has been malted, brewers may roast their malts to bring out different flavors.

The Shape of Barley

How and when the grain is grown makes a difference in its development of protein and starches, as well as the general yield of a single barley plant. Like most cereal grains, barley comes from a wild grass that has been cultivated for thousands of years for its nutritional value.

And over that time, we’ve developed three distinct shapes of barley stalks within the species.

Six-Row

As the name implies, a stalk of six-row barley has six distinct heads from which it produces grain. Thanks to the crowded nature of the plant, the kernels of barley tend to be thinner, longer, and may be less uniform in shape.

The smaller size means you get less flavor extract from six-row barley, but the smaller kernels tend to have higher concentrations of protein, enzymes, and beer coloring potential.

The irrigation of the land may affect the size and shape of the kernels; access to more water may mean plumper, lower protein barley.

Two-Row

While it is still the same kind of plant, two-row barley was bred from an earlier version of “traditional” two-row European barley. It was bred specifically for a larger grain yield than the traditional variety, a lower protein content, and a higher malt extract release.

Because these stalks only produce two rows of kernels, they tend to be larger and more uniform in size than six-row barley.

Fun fact: the breeding of this plant made brewing American light lagers an easier task and kicked off a revolution of less sweet beers in Japan, known as dry beers.

Winter Two-Rows and Six-Rows

The names give it away. Farmers bred these varieties of barley to survive and germinate in freezing conditions. When you compare barley to rye or wheat, it’s still generally less tolerant of cold weather, but it’s good enough for farmers to grow barley in less temperate areas year-round.

These hardier stalks help barley farmers protect their soil during the winter months, reduces the need for intense irrigation, and even produces higher kernel yields than regular varieties. Since it’s less expensive to grow, the malt tends to be cheaper as well.

Ready to improve your all-grain brewing process and dial in your system?

This video course covers techniques and processes for water chemistry, yeast health, mashing, fermentation temperature, dry-hopping, zero-oxygen packaging and more!

Click Here to Learn More3 Ways Malt Defines Your Beer

Just like your recipe, the type of malt you use can totally change the character of your beer. The major component of malt—sugar—goes on to determine the flavor and color of your beer.

1. Sugar Content

Malt feeds your beer. Without malt and its unlocked sugars to feed on, your yeast would starve. And the structures of the sugars inside the malt go on to determine the flavor, aroma, and color of your brew.

Sure, you can find plenty of substitutes for malt in your brew. But if you were so set on that, you wouldn’t be here, right?

2. Flavor and Aroma

How your malted barley is processed determines what kind of flavors and aromas it adds to your brew. Sure, all barley needs germination to become a malt, but how you dry or heat the malt afterwards makes a huge difference.

For example, if a maltster—a person who malts barley—puts undried, freshly germinated kernels directly into a kiln, most of the starch converts to liquid sugar, eventually caramelizing. This can give your beer buttery-, toffee-, or raisin-like aromas.

In another scenario, the maltster might dry the kernels before heating them. The starches in the kernels undergo what’s called the Maillard reaction. Chemically, sugars and amino acids react within the kernel. In simple terms, this is toasting or roasting your malt. We get chocolate, coffee, and unsurprisingly, toast aromas from this process.

3. Color

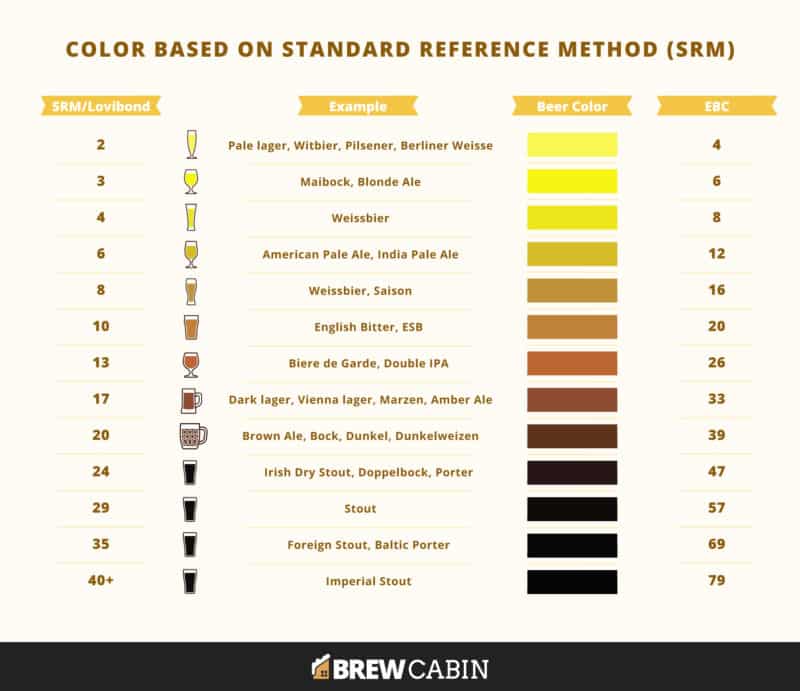

So you’re perusing brewing malts online. You look at the description of a malt and see a Lovibond rating with a number between two and 70. Or maybe you seen an EBC between four and 138.

What the heck is a Lovibond and an EBC?

Lovibond is actually the name of a company that produces color measurement equipment. The Lovibond rating—at least for US malts—is actually a weird shorthand for ASBC SRM, or the American Society of Brewing Chemists Standard Reference Method.

Alternatively, EBC is the European Brewing Convention, a standard for defining the color of beer developed by the Institute of Brewing and the European Brewing Convention.

The numerical ratings that both SRM and EBC give to a malt tell you roughly how light or dark of a beer it can produce. A Lovibond machine performs a photometric evaluation of the sample, which is just measuring the absorption of light in a particular beer.

The science of measuring light absorption and sample wavelengths gets a little complex and honestly unnecessary for us from there. (That’s what the machine is for.) What you need to know is the higher on the SRM or EBC scale, the darker the beer. For example, a 3 SRM/6 EBC beer would be a Pilsner while a 29 SRM/57 EBC beer would be a porter.

Another handy bit of knowledge: converting between the SRM and EBC scale is possible and pretty simple:

SRM = (EBC rating) x 1.97

EBC = (SRM rating) ÷ 1.97

Or you could use an online calculator like this one.

To get the best sense of what these ratings mean, though, it’s best to look at an actual color chart.

A little malt for coloring goes a long way. This is why you might have a recipe that calls for several pounds of grain or a pale malt, but only a few ounces of an extremely dark malt.

Every Beer Malt (So Far)

So now that you’re a veritable expert on the concepts behind malt, it’s time to actually look at every beer malt we could find. If you ever get lost, don’t be afraid to refer back to how we color beer or define different shapes of barley.

We’ve categorized the malts by the general process used to make them, which should hopefully make it easier for you to understand when and how to use these malts.

Note: We will not cover or recommend specific malt years, even though the American Malting Barley Association does so in their annual malt recommendations.

To view the spreadsheet we built that contains not only every brewing malt, but also hops, yeast, extracts, and adjuncts, click here.

Standard Processed Malts

Sometimes called white malts. They have enough power to convert their own starches, which means you can use them as your base for all-grain brewing without any problems.

They are often used as a base grain for beers using more heavily flavored roasted malts.

Pilsner Malt

As the name suggests, this kind of malt is one of the simplest ways to obtain a Czech or Pilsner. These malts brew pale and have a delicate flavor, making them perfect for clean lagers and pale ales.

Pale Malts

You will find even more varieties of pale malts inside the main family, including British Pale, American 2-Row Pale, and American 6-Row Pale. However, these varieties are all used in the production of light ales that are focused on biscuit and honey flavors.

To keep them straight, remember:

- British Pale tends to be darker than American Pales, but more flavorful.

- American 2-Row Pale is somewhere between a pilsner and a British Pale with honey and grain flavors.

- American 6-Row Pale is the king of pale malt when it comes to converting starch to sugars, but less flavorful than the 2-Row.

Pale Ale Malts

Not to be confused with the plain-old pale variety, pale ale malts are developed specifically for English-style pale ales. They’re darker than pale malts and have a more tempered malty flavor.

Melanoidin Malts

Also called Vienna or Munich malts has high—you guessed it—melanoidin content. This is a chemical produced when sugars and amino acids combine at high temperatures. They’re the foundation for amber lagers that require sweet caramel flavors without the dark coloring.

Kilned at a higher temperature than pale malts, a Vienna malt can be used to add a little complexity to your brew flavor or make up the entirety of your grain bill. It’s a good place to start if you want to try a Vienna lager, but it might help you create biscuity, toasty flavors in an Oktoberfest or Marzen-style beer.

If you keep heating Vienna malt, you’ll eventually end up with Munich malt. The malt ends up being a much darker color and provides rich, bready flavors perfect for dunkel or Oktoberfest beer.

Watch out though: Munich malts come in both “light” and “dark” varieties. This is because the kilning times and intensity can vary from malthouse to malthouse. (Did we also mention this is confusing? Be sure to check the color rating before you build a recipe with it.)

Caramel Malts

Instead of kilning, maltsters produce caramel malts by mashing the green malt—the germinated grain—and roasting it in a drum roaster.

Special Glassy Malts

The high-moisture and low-temperature conditions in the roaster give the kernels a glassy appearance. These malts are used as boosters, either to maintain your beer’s head, add more body to your brew, or make your final product sweeter.

Caramel/Crystal Malts

Bringing both flavor and color to the table, crystal or caramel malts are made through raising the temperatures of green malt to create more sugars and amino acids. Depending on how long the malt is heated, it can range from light to dark-colored malts.

The lighter caramel malts tend to be used for the main flavor of a beer, while the darker varieties are more for supporting flavors. Dark crystals can easily overwhelm your beer, so you want to use them in moderation.

Special Hybrid Malts

While they’re similar to caramel malts, special malt also have the characteristics of roasted malts. That’s because they’re processed by caramelizing and then roasting. So while they may have some of the sweet breadiness from caramel malts, you can also get the rich and dried fruit flavors of roasted malts.

Roasted Malts

The name of the family is pretty self-explanatory: these malts are achieved by roasting pale malts. While this destroys their potential to process sugars, they instead develop dry, bitter, and cocoa flavors.

Biscuit Malt

Kilned at up to 440ºF (227ºC), biscuit malts are named for their biscuit flavor. While the taste is similar to a Vienna malt, the flavor is much more intense.

Amber Malt

This malt is fairly similar to a biscuit malt, although amber malts are drum roasted in the English malting tradition. They are less dry than biscuit malts, but have more complex flavors—including toffee, nuts, and baked bread—as well as more bitter characteristics.

Brown Malt

If you leave amber malt in the drum roaster for too long, you’ll end up with brown malt. You can add a little complexity to your dark beers by using a little brown malt.

Chocolate Malt

You don’t (typically) get chocolate flavors by actually using chocolate. You use chocolate malt instead. It has a slight burnt flavor and a little bit of astringency.

Black Malt

If you’re looking for a deep color addition to your next stout, look no further than black malt. Using huskless barley reduces the bitterness of black malt, so you can get a stout with bright and refreshing flavors.

Roasted Barley

Technically this isn’t a malt. That’s because roasted barley is processed without triggering any germination.

Special Process Malts

In a huge twist none of us ever saw coming, special process malts are made using special processes. (Please play along and gasp for dramatic effect.) These tend to be relatively expensive malts since there’s not much of a market for them, but they’re definitely worth mentioning.

Just remember: even the tiniest bit goes a long way. Use these very carefully!

Acidulated Malt

Also called Sauermalz, German for sour malt, acidulated malt is used to add acid to beer. Maltsters cultivate these flavors by spraying sour wort over the barley while it’s germinating. It’s super-potent, so even a little bit can add a sharp flavor and significantly reduce your mash pH.

Smoked Malt

After germination, the green malt is either completely or partially dried using a wood fire for a smoky flavor. Maltsters may use different woods to bring out different flavors. And speaking of flavors, smoked malt is a love-it or hate-it kind of malt. Some people just can’t get past the flavor, while others love it for the unique characteristics it adds to a beer.

Lightly smoked malts can make up 100 perfect of your grain bill, but only if it’s very lightly smoked. Always refer to the maltster for use recommendations unless you enjoy making undrinkable beer.

Peated Malt

It’s technically more of a subtype of smoked malt rather than a type of its own. Peated malt is smoked using—you guessed it—peat.

Non-Barley Malts

When malted barley just isn’t driving your beer creativity, you can always use malts made from other grains. Like barley, they can be processed in different ways, so these malts can have a variety of colors and flavors.

- Wheat Malt can be difficult to work with, especially if you’re not a fan of breaking out the mash tun. However, they have a high protein content if you’re looking for a stronger bready flavor.

- Rye Malt works well with bold hops and can add a spice to your brew. It doesn’t have a husk, so it’s difficult to lauter.

- Oat Malt fills out your beer’s flavor and gives it a soft and silky mouthfeel. If you’re into smooth small batches, using an oat malt may be worth all the extra lautering.

- Distillers Malt is technically made from barley, but it’s not malting barley. This lower-grade malt isn’t generally used in beer, since most of the flavor is lost during distillation and the leftover flavor is kind of grassy.

- Chit Malt is another technically made-from-barley malt. However, it relies on a short germination schedule to give it the characteristics of an unmalted adjunct. It’s hard to work with, more expensive, and probably not worth your precious homebrewing time.

A Word About Organic Malts

Actually, we have several words about organic brewing malts. The term organic is exceptionally vague at best, and misleading at worst. Depending on the country you live in, organic as a marketing term can vary, so try to pay close attention to what organic actually means in your area.

Organic may mean the malt grain was grown through sustainable farming practices with absolutely no pesticides. It may also mean the malt grain was grown on a massive farm using specifically approved pesticides.

Just remember: organic doesn’t automatically mean better. If you’re going to spend more for organic malted barley, just make sure you understand why they’re using the label, when your local farmers are able to use the term organic, and if the pricer malt is worth it for you (and your homebrew budget).

Release Your Inner Maltist

Now that you know what to look for—color, malt process, usage amount—and we all have enough knowledge to dream about nothing but malts varieties for months. Who’s complaining?

Happy Brewing!